Below is the online edition of In the Beginning: Compelling Evidence for Creation and the Flood,

by Dr. Walt Brown. Copyright © Center for Scientific Creation. All rights reserved.

Click here to order the hardbound 8th edition (2008) and other materials.

General Description

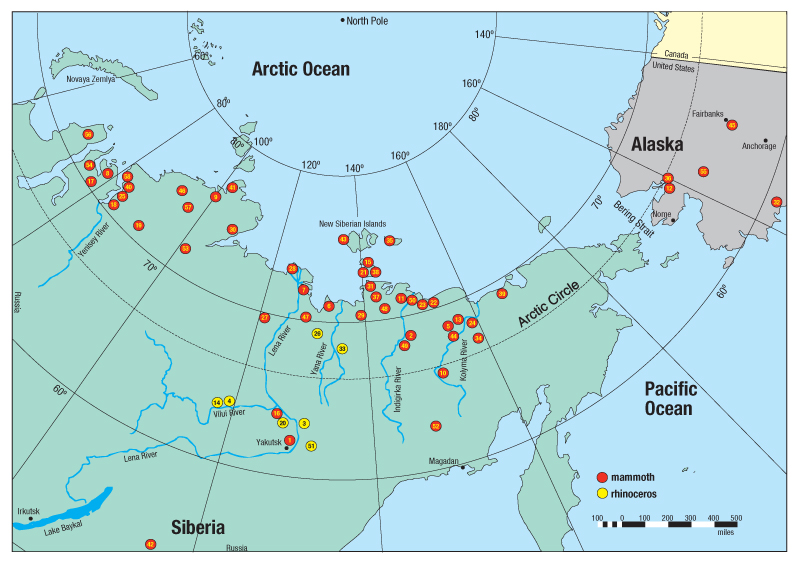

What Is Found. Since 1800, at least 11 scientific expeditions have excavated fleshy remains of extinct mammoths.9 Most fleshy remains were buried in the permafrost of northern Siberia, inside the Arctic Circle. The remains of six mammoths have been found in Alaska. Only a few complete carcasses have been discovered. Usually, wild animals had eaten the exposed parts before scientists arrived.

If we look in the same region for frozen soft tissue of other animals, we learn that several rhinoceroses have been found, some remarkably preserved. (Table 10 on page 270 summarizes 57 reported mammoth and rhinoceros discoveries.) Other fleshy remains come from a horse,10 a young musk ox,11 a wolverine,12 voles,13 squirrels, a bison,14 a rabbit, and a lynx.15

|

|

Datea |

Nameb |

Description (Pertains to mammoths unless stated otherwise.) |

Referencec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

1693d |

Ides |

frozen head and lege |

Ides, 25–27 |

| 2 |

1723 |

Messerschmidt |

frozen head and big pieces of skin with long hair |

Breyne, 138 |

| 3 |

1739 |

Laptev |

several rhinoceros heads |

T, 22 |

| 4 |

1771 |

Pallas |

complete rhinoceros; suffocated; hairy head and two feet recovered |

Eden;17 H, 44, 82, 184 |

| 5 |

1787 |

Sarychev |

complete when first seen; uprighte |

H, 82–83; T, 23 |

| 6 |

1800 |

Potapov |

“on the shores of the Polar Sea”; skin and hair recovered |

T, 25 |

| 7 |

1805 |

Adams |

complete when first seen; 70-year-old male; 35,800 RCY; uprighte |

T, 23–25; H, 83–85 |

| 8 |

1839 |

Trofimov |

complete; in a river bank; hair, bones, pieces of flesh and brain recovered |

H, 85; T, 26 |

| 9 |

1843 |

Middendorff |

a half-grown mammoth; most of its flesh had decayed, eyeball recovered |

H, 85–86; Eden, 104 |

| 10 |

1845d |

Khitrof |

well preserved when found; food between teeth |

H, 86 |

| 11 |

1846 |

Benkendorf |

complete; upright; see page 273 |

HD, 32–38; D, 97–103 |

| 12 |

1847d |

Goodridge |

AK; “a skull with a quantity of hair” |

Maddren18 |

| 13 |

1854 |

Khitrovo |

a foot covered with hair; from a mammoth in good condition |

T, 27 |

| 14 |

1858 |

Vilui |

rhinoceros; a complete skeleton with some ligaments |

T, 27 |

| 15 |

1860 |

Boyarski |

upright in the face of an island’s coastal cliff |

T, 32 |

| 16 |

1861d |

Golubef |

“a huge beast covered with skin” in a river bank |

H, 86 |

| 17 |

1864 |

Schmidt-1 |

PC; only skin and hair recovered a year later |

T, 28; D, 108–110 |

| 18 |

1865 |

Koschkarof |

PC; largely decomposed a year later |

H, 86–87 |

| 19 |

1866 |

Schmidt-2 |

recovered on a lake shore; bones and hair of various lengths |

T, 28; P, 8 |

| 20 |

1866 |

Kolesov |

a large mammoth or rhinoceros, covered with skin |

T, 27 |

| 21 |

1866 |

Bunge-1 |

“pieces of skin and plenty of hair” |

T, 32 |

| 22 |

1869 |

Von Maydell-1 |

PC; upright; three years later, only a large hairy hide recovered |

D, 80–95; H, 87–89 |

| 23 |

1869 |

Von Maydell-2 |

PC; only two legs found a year later |

D, 80–95; H, 87–89 |

| 24 |

1870 |

Von Maydell-3 |

PC; only a leg was recovered three years later |

D, 80–95; H, 87–89 |

| 25 |

1876 |

Nordenskiold |

inch-thick hide near skull of a musk sheep |

Nordenskiold, 310; H, 89 |

| 26 |

1877 |

Von Schrenck |

complete rhinoceros; the head was thoroughly studied; apparent suffocation |

H, 89; T, 30–31 |

| 27 |

1879 |

Bunge-2 |

tusks chopped off; reported to authorities four years later |

T, 31 |

| 28 |

1884 |

Bunge-3 |

PC; first seen by natives 27 years earlier; two-inch-thick skin claimed |

T, 16, 31 |

| 29 |

1886 |

Toll-1 |

23 years after natives’ discovery, a few soft parts and hair were recovered |

T, 32 |

| 30 |

1889 |

Burimovitch |

reportedly complete; Toll’s bad health prevented him from reaching the site |

T, 33 |

| 31 |

1893 |

Toll-2 |

damaged bones, hairy skin, and other hair |

T, 33 |

| 32 |

1894 |

Dall |

AK; disintegrated muscle tissue, bones, and 300 pounds of fat |

Dall19 |

| 33 |

1901 |

Pfizenmayer |

rhinoceros; “a few fragments of ligaments and other soft parts” |

P, 53–54; T, 35 |

| 34 |

1901 |

Berezovka |

almost complete; upright; late summer death; 44,000 RCY; see page 273 |

HE, 611–625; D, 111–136 |

| 35 |

1902 |

Brusnev |

hair recovered, mixed with mud |

T, 36 |

| 36 |

1908 |

Quackenbush |

AK; pieces of flesh; tendons, skin, tail, and hair recovered |

A, 299; Q, 107–113 |

| 37 |

1908 |

Vollosovitch-1 |

small female; pieces scattered; died at end of summer; 29,500 and 44,000 RCY |

P, 146–164; D, 211–212 |

| 38 |

1910 |

Vollosovitch-2 |

late summer death; well-preserved eye, four legs, trunk, food in stomach |

P, 241–246; T, 37–38 |

| 39 |

1910 |

Soloviev |

PC; young mammoth; reported to but not pursued by scientists |

T, 39 |

| 40 |

1913 |

Goltchika |

PC; “dogs and foxes got at it and ate pretty well all the lot” |

T, 38; D, 212 |

| 41 |

1915 |

Transehe |

PC; found in 30- to 50-foot cliff on the Arctic Ocean; never excavated |

T, 39; Transehe20 |

| 42 |

1922 |

Kara |

carcass reported to scientists, but only hard parts remained four years later |

T, 39–40 |

| 43 |

1923 |

Andrews |

ivory traders sold skull still containing ligaments to British museum |

T, 39 |

| 44 |

1924 |

Middle Kolyma |

scrap of trunk remained; no record of original discovery |

VT, 19; G, 26 |

| 45 |

1948 |

Fairbanks Creek |

AK; 200-pound, 6-month-old; head, trunk, and one leg; 15,380 RCY and 21,300 RCY |

A, 299–300; G, 38–41 |

| 46 |

1949 |

Taimir |

50-year-old male; tendons (11,500 RCY), hair, and an almost complete skeleton |

VT, 20; Lister and Bahl21 |

| 47 |

1960 |

Chekurov |

carcass of a young female; very small tusks; hair dated at 26,000 RCY |

Vinogradov22 |

| 48 |

1970 |

Berelekh |

a cemetery of at least 156 mammoths; minor hair and flesh remains |

U, 134–148; S, 66–68 |

| 49 |

1971 |

Terektyakh |

pieces of muscle, ligament, and skin; some around head |

S, 67 |

| 50 |

1972 |

Shandrin |

old; 550 pounds of internal organs and food preserved; 32,000 RCY and 43,000 RCY |

U, 67–80; G, 27–29 |

| 51 |

1972 |

Churapachi |

old rhinoceros, probably a female; “lower legs were in fair condition” |

G, 34–37 |

| 52 |

1977 |

Dima |

complete; 6-to-8-month-old male; 26,000 RCY and 40,000 RCY; see page 268 |

G, 7–24; U, 40–67 |

| 53 |

1978 |

Khatanga |

55- to 60-year-old male; left ear, two feet; trunk in pieces; 45,000 RCY and 53,000 RCY |

U, 30–40; G, 24–27 |

| 54 |

1979 |

Yuribei |

12-year-old female; green-yellow grass in stomach; hind quarters preserved |

U, 12–13, 108–134; VT, 22 |

| 55 |

1983 |

Colorado Creek |

AK; two males; bones, hair, and gut contents recovered; 16,150 RCY and 22,850 RCY |

Thorson and Guthrie23 |

| 56 |

1988 |

Mascha |

3- to 4-month-old female; complete except for trunk, tail, and left ear; found in the Yamal Peninsula |

LB, 46–47; VT, 25 |

| 57 |

1999 |

Jarkov |

fragments of a 47-year-old male; removed in a 23-ton block of permafrost by helicopter |

Stone24 |

| 58 |

2012 |

Zhenya |

15-year-old male, 1100 pounds, died in summer, right half of body well preserved (organs, skin, tusk) |

Moscow News, 17 Oct. 2012 |

| Some references in the right column are abbreviated: A=Anthony, D=Digby, G=Guthrie, H=Howorth, HD=Hornaday, HE=Herz, LB=Lister and Bahl, P=Pfizenmayer, Q=Quackenbush, S=Stewart, 1977, T=Tolmachoff, U=Ukraintseva, VT=Vereshchagin and Tikhonov. Page numbers follow each abbreviation. See endnotes for complete citation. Other abbreviations are AK=found in Alaska, PC=possibly complete when first seen, RCY=radiocarbon years (most radiocarbon ages are from VT: 17–25).

Footnotes: a. Usually the year of excavation. First sighting often occurred earlier. b. The name given is usually the discoverer’s, a prominent person involved in reporting the discovery, or a geographical name, such as that of a river. |

||||

If we now look for the bones and ivory of mammoths, not just preserved flesh, the number of discoveries becomes enormous, especially in Siberia and Alaska. Nikolai Vereshchagin, Chairman of the Russian Academy of Science’s Committee for the Study of Mammoths, estimated that more than half a million tons of mammoth tusks were buried along a 600-mile stretch of the Arctic coast.16 Because the typical tusk weighs 100 pounds, this implies that about 5 million mammoths lived in this small region. Even if this estimate is high or represents thousands of years of accumulation, we can see that large herds of mammoths must have thrived along what is now the Arctic coast. Mammoth bones and ivory are also found in Europe, North and Central Asia, and in North America, as far south as Mexico City.

Dense concentrations of mammoth bones, tusks, and teeth are also found on remote Arctic islands. Obviously, today’s water barriers were not always there. Many have described these mammoth remains as the main substance of the islands.25 What could account for any concentration of bones and ivory on barren islands well inside the Arctic Circle? Also, more than 200 mammoth molars were dredged up along with oysters from the Dogger Bank in the North Sea.26

The northern portions of Europe, Asia, and North America contain bones of many other animals along with those of mammoths. A partial listing includes tiger,27 antelope,28 camel, horse, reindeer, giant beaver, fox, giant bison, giant ox, musk sheep, musk ox, donkey, badger, ibex, woolly rhinoceros, lynx, leopard, wolverine, Arctic hare, lion, elk, giant wolf, ground squirrel, cave hyena, bear, and many types of birds. Friend and foe, as well as young and old, are found together. Carnivores are sometimes buried with herbivores. Were their deaths related? Rarely are animal bones preserved; preservation of so many different types of animal bones suggests a common explanation.

Finally, corings 100 feet into Siberia’s permafrost, have recovered sediments mixed with ancient DNA of mammoths, bison, horses, other temperate animals, and the lush vegetation they require. Nearer the surface, these types of DNA are absent, but DNA of meager plants able to live there today is present.29 The climate must have suddenly and permanently changed to what it is today.

Mammoth Characteristics and Environment. The common misconception that mammoths lived in areas of extreme cold comes primarily from popular drawings of mammoths living comfortably in snowy, Arctic regions. The artists, in turn, were influenced by earlier opinions based on the mammoth’s hairy coat, thick skin, and a 3.5-inch layer of fat under the skin. However, animals with these characteristics do not necessarily live in cold climates. Let’s examine these characteristics more closely.

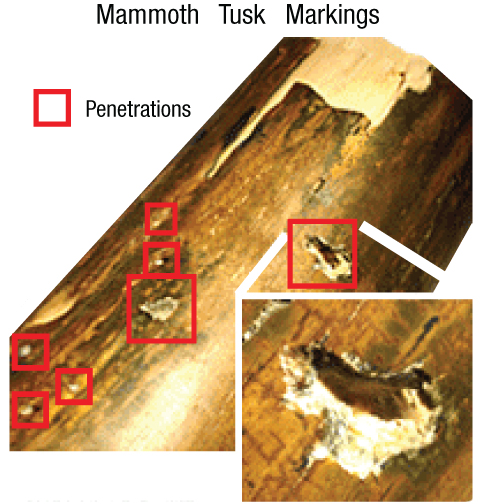

Figure 157: Peppered Mammoth Tusk. Scientists are finding, over wide geographical areas, mammoth tusks embedded on one side with millimeter-size particles rich in iron and nickel. This has led some to wonder if meteorites exploding high in the atmosphere punctured those tusks.32 The British Broadcasting Corporation stated, “Startling evidence has been found which shows mammoth and other great beasts from the last ice age were blasted with material that came from space.”33 But is that the whole story?

Hair. The mammoth’s hairy coat no more implies an Arctic adaptation than a woolly coat does for a sheep. Mammoths lacked erector muscles that fluff up an animal’s fur and create insulating air pockets. Neuville, who conducted the most detailed study of mammoth skin and hair, wrote: “It appears to me impossible to find, in the anatomical examination of the skin and pelage [hair], any argument in favor of adaptation to the cold.”30 Long hair on a mammoth’s legs hung to its toes.31 Had it walked in snow, snow and ice would have caked on its hairy “ankles.” Each step into and out of snow would have pulled or worn away the “ankle” hair. All hoofed animals living in the Arctic, including the musk ox, have fur, not hair, on their legs.34 Fur, especially oily fur, holds a thick layer of stagnant air (an excellent insulator) between the snow and skin. With the mammoth’s greaseless hair, much more snow would touch the skin, melt, and increase the heat transfer 10-to-100 fold. Later refreezing would seriously harm the animal.

Skin. Mammoth and elephant skin are similar in thickness and structure.35 Both lack oil glands, making them vulnerable to cold, damp climates. Arctic mammals have both oil glands and erector muscles—equipment absent in mammoths.36

Fat. Some animals living in temperate or even tropical zones, such as the rhinoceros, have thick layers of fat, while many Arctic animals, such as reindeer and caribou, have little fat. Thick layers of fat under the skin simply show that food was plentiful. Abundant food implies a temperate climate.

Elephants. The elephant, which is closely related to the mammoth,37 lives in tropical or temperate regions, not the Arctic. It requires a climate that ranges from warm to hot, and “it gets a stomach ache if the temperature drops close to freezing.”38 Newborn elephants are susceptible to pneumonia and must be kept warm and dry.39 Hannibal crossed the Alps with 37 elephants; the cold weather killed all but one.40

Water. If mammoths lived in an Arctic climate, their drinking water in the winter must have come from eating snow or ice. A wild elephant requires 30–60 gallons of water each day.41 The heat needed to melt snow or ice and warm it to body temperature would consume about half a typical elephant’s calories. The mammoth’s long, vulnerable trunk would bear much of this thermal (melting) stress. Nursing elephants require about 25% more water.

Salt. How would a mammoth living in an Arctic climate satisfy its large salt appetite? Elephants dig for salt using their sharp tusks.42 In rock-hard permafrost this would be almost impossible, summer or winter, especially with curved tusks.

Nearby Plants and Animals. The easiest and most accurate way to determine an extinct animal’s or plant’s environment is to identify familiar animals and plants buried nearby. For the mammoth, this includes rhinoceroses, tigers, horses, antelope,43 bison, and temperate species of grasses. All live in warm climates. Some burrowing animals are frozen, such as voles, which would not burrow in rock-hard permafrost. Even larvae of the warble fly have been found in a frozen mammoth’s intestine—larvae identical to those found in tropical elephants today.45 No one argues that animals and plants buried near the mammoths were adapted to the Arctic. Why do so for mammoths?

Temperature. The average January temperature in northeastern Siberia is about -28°F (60°F below freezing)! During the Ice Age, it was even colder. The long, slender trunk of the mammoth was particularly vulnerable to cold weather. A six-foot-long nose could not survive even one cold night, let alone an eight-month-long Siberian winter or a sudden cold snap. For the more slender trunk of a young mammoth, the heat loss would be more deadly. An elephant usually dies if its trunk is seriously injured.46

No Winter Sunlight. Cold temperatures are one problem, but six months of little sunlight during Arctic winters is quite another. While some claim that mammoths were adapted to the cold environment of Siberia and Alaska, vegetation, adapted or not, does not grow during the months-long Arctic night. In those regions today, vegetation is covered by snow and ice ten months each year. Mammoths had to eat voraciously. Elephants in the wild spend about 16 hours a day foraging for food in relatively lush environments, summer and winter.47

Three Problems. Before examining other facts, we can see three curious problems. First, northern Siberia today is cold, dry, and desolate. Vegetation does not grow during dark Arctic winters. How could millions of mammoths and other animals, such as rhinoceroses, horses, bison, and antelope, feed themselves? But if their environment were more temperate and moist, why did it change?

Second, the well-preserved mammoths and rhinoceroses must have been completely frozen soon after death or their soft internal parts would have quickly decomposed. Guthrie has written that an unopened animal continues to decompose long after a fresh kill, even in very cold temperatures, because its internal heat can sustain microbial and enzyme activity as long as the carcass is completely covered with an insulating pelt.48 Because mammoths had such large reservoirs of body heat, the freezing temperatures must have been extremely low.

Finally, their bodies were buried and protected from predators, including birds and insects. Such burials could not have occurred if the ground were perpetually frozen as it is today. Again, this implies a major climate change, but now we can see that it must have changed dramatically and suddenly. How were these huge animals quickly frozen and buried—almost exclusively in muck, a dark soil containing decomposed animal and vegetable matter?

Muck. Muck is a major geological mystery. It covers one-seventh of the earth’s land surface—all surrounding the Arctic Ocean. Muck occupies treeless, generally flat terrain, with no surrounding mountains from which the muck could have eroded. Russian geologists have drilled through 4,000 feet of this muck without hitting solid rock. Where did so much eroded material come from? What eroded it?

Oil prospectors, drilling through Alaskan muck, have “brought up an 18-inch-long chunk of tree trunk from almost 1,000 feet below the surface. It wasn’t petrified—just frozen.”49 The nearest forests are hundreds of miles away. Williams describes similar discoveries in Alaska:

Though the ground is frozen for 1,900 feet down from the surface at Prudhoe Bay, everywhere the oil companies drilled around this area they discovered an ancient tropical forest. It was in frozen state, not in petrified state. It is between 1,100 and 1,700 feet down. There are palm trees, pine trees, and tropical foliage in great profusion. In fact, they found them lapped all over each other, just as though they had fallen in that position.50

How were trees buried under a thousand feet of hard, frozen ground? We are faced with the same series of questions we first saw with the frozen mammoths. Again, it seems there was a sudden and dramatic freezing accompanied by rapid burial in muck, now frozen solid.

Figure 158: Fossil Forest, New Siberian Islands. Vast, floating remains of forests have washed up on the New Siberian Islands, well inside the Arctic Circle and thousands of miles from comparable forests today. This driftwood was washed ashore on Bolshoi Lyakhov Island, one of the New Siberian Islands. The wood was probably buried under the muck that covers northern Siberia. Northward flowing Siberian rivers, during early summer flooding, eroded the muck, releasing the buried forests. “Fossil wood,” as it is called, is a main source of fuel and building material for many Siberians.

Figure 159: Fossil Forest, Kolyma River. Here, driftwood is at the mouth of the Kolyma River, on the northern coast of Siberia. Today, no trees of this size grow along the Kolyma. Leaves, and even fruit (plums), have been found on such floating trees.44 One would not expect to see leaves and fruit if these trees had been carried far by rivers. Why didn’t these trees decay?