Below is the online edition of In the Beginning: Compelling Evidence for Creation and the Flood,

by Dr. Walt Brown. Copyright © Center for Scientific Creation. All rights reserved.

Click here to order the hardbound 8th edition (2008) and other materials.

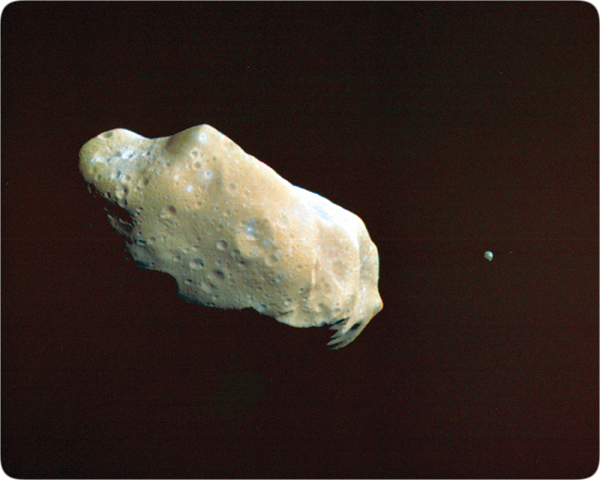

Figure 179: Asteroid Ida and Its Moon, Dactyl. In 1993, the Galileo spacecraft, heading toward Jupiter, took this picture 2,000 miles from asteroid Ida. To the surprise of most, Ida had a moon (about 1 mile in diameter) orbiting 60 miles away! Both Ida and Dactyl are composed of earthlike rock. We now know that at least 243 other asteroids have moons; ten of them have two moons.1 According to the laws of orbital mechanics (described in the preceding chapter), capturing a moon in space is unbelievably difficult—unless both the asteroid and a nearby potential moon had very similar speeds and directions and unless gases, which can provide aerobraking, surrounded the asteroid, so the potential moon could be slowed down enough to be captured. If so, the asteroid, its moon, and each gas molecule were probably coming from the same place and were launched about the same time. Within a million years, passing bodies would have stripped the moons away, so these asteroid-moon captures must have been relatively recent.

From a distance, an asteroid looks like a big rock. However, many show, by their low density, that they contain something light, such as water-ice or empty space.2 Also, the best close-up pictures of an asteroid show millions of smaller rocks on its surface. Can you guess why many are well rounded? Asteroids are literally flying rock piles held together by gravity. Ida, about 35 miles long, does not have enough gravity to squeeze itself into a spherical shape.